|

| photo by Alice Lum |

While the young Samuel Jones Tilden was studying law at Yale University and then at New York University in the 1830s, Samuel Ruggles’ grand plan for Gramercy Square, later renamed Gramercy Park, was well underway.

Tilden sprang from an old colonial family—Nathaniel Tilden had come to America from England in 1634. Now, in the first half of the 19th century Tilden’s family had grown financially comfortable as manufacturers and sellers of Tilden’s Extract, a popular patent medicine. By the decade before the Civil War Tilden had a thriving legal practice and represented many railroad concerns.

His passion, however, was rooted as much in politics as in law. In 1846 he was a member of the New York State Assembly and, by now, Gramercy Square was fully developed. The landscaped park surrounded by a handsome iron fence was lined with brownstone mansions. The semi-private enclave lured some of the city’s wealthiest and most influential citizens. The bachelor politician-lawyer purchased No. 15 on the south side of the park from the Belden Family in 1863 for $37,500 (about $552,000 today).

Built in 1844 the brownstone-fronted residence, along with its neighbor next door at No. 16, was designed in the Gothic Revival style. Square-headed eyebrows capped the windows and Gothic-style tracery edged the cornice. Over the entrance way the Belden coat of arms was carved into the keystone.

Tilden added a dining room to the rear and, below ground, “a wine cellar of suitable size, to serve a well-to-do man of conservative tastes,” according to a close friend years later.

Tilden’s rear gardens were notable. Helen W. Henderson, in her 1917 “A Loiterer in New York,” remembered “The gardens in the rear of the Tilden house were the largest in the row, extending through the block to Nineteenth Street, and were charmingly laid out with box-bordered walks and flower-beds, and shaded by large trees.”

Following the war he became chairman of the Democratic State Committee. Although he had enjoyed a friendly working relationship with William M. Tweed, it all came to an ugly end with Tilden heading a reform movement in the Democratic Party and making himself an enemy of what became known as the “Tweed Ring.”

In 1874 Tilden purchased the Hall mansion next door at No. 14 for $50,000. His friend, George Smith later recalled that “Mr. Tilden, although a bachelor, found in the course of time that he required more space than his house afforded him.”

Tilden’s intentions of creating one large mansion from the two would have to wait. In the autumn of that year he was elected Governor of New York. He rented the houses for two years while he held office.

His term as governor would be short-lived. He stepped down to run for President in 1876 to succeed Grant. There was little doubt that Tilden won the election. In 1907 Brentano’s “Old Buildings of New York City” remarked “…he received a majority of the popular vote, but owing to the fact that the votes of several States were disputed, the celebrated Electoral Commission was appointed, consisting of senators, judges, and representatives. The commission divided on party lines and gave the disputed votes to Mr. Hayes.”

|

| campaign poster from the collection of the Library of Congress |

Helen Henderson explained “There seems to be but little doubt that Tilden was elected, but party feeling was so strong it was feared that, had he been sustained, another civil war would have resulted.”

So, to maintain civil harmony, the clear loser in the presidential election, Rutherford B. Hayes, was inaugurated. And Tilden returned to his home on Gramercy Park. On June 12, 1877 he gave what was considered his concession speech at the Manhattan Club; however the feisty politician pulled no punches in regard to his feelings.

In part he said “I disclaim any thought of the personal wrong involved in this transaction. Not by any act of word of mine shall that be dwarfed or degraded into a personal grievance, which is, in truth, the greatest wrong that has stained our national annals. To every man of the four and a quarter millions who were defrauded of the fruits of their elective franchise it is as great a wrong as it is to me. And no less to every man of the minority will the ultimate consequences extend.”

|

| On October 27, 1877 New Yorkers serenaded Tilden in front of his residence. The house to the left, No. 16 which would later become the Players club, was owned by Clarkson N. Potter at the time. The following year Tilden would join Nos. 14 and 15 as one mansion -- sketch from the NYPL collection |

Tilden returned to New York, but according to George Smith, “another year elapsed before the remodeling and connecting of the buildings began.“ He commissioned Calvert Vaux to renovate the two residences into a single 40-room mansion—ample living space for an unmarried man.

Perhaps unfortunately the genius of Vaux will forever be remembered almost solely for his work on Central Park.

But his far-sighted designs stepped away from the comfortable traditions and provided refreshing and exciting results.

For the Tilden mansion he turned to Victorian Gothic, a slight variation of the style popularized by John Ruskin.

Three years later Vaux would bring the style to culmination with his extraordinary

Jefferson Market Courthouse.

Tilden’s finished residence stood out among the prim and proper brownstones along the park. Vaux used brownstone and “red-stone” for the façade, trimmed with red and gray granite that created contrasting belt courses and panels. The façade was encrusted with carved portraits—Shakespeare, Dante, Benjamin Franklin, Milton and Goethe among them—and floral and geometric designs.

|

| photo by Alice Lum |

The New-York Tribune called the house “magnificent” and reported on its hardwood trim, carved ceilings, parquet flooring, carved mantels, tapestry walls, five bathrooms, laundry and “drying-room.” The New York Times said it was “most lavishly decorated."

|

| photo http://www.dnainfo.com/new-york/20110130/murray-hill-gramercy/clampdown-at-national-arts-club-board-meeting-after-scandal/slideshow/popup/57629 |

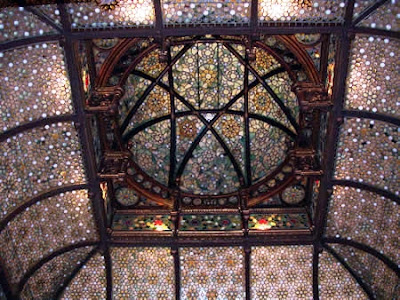

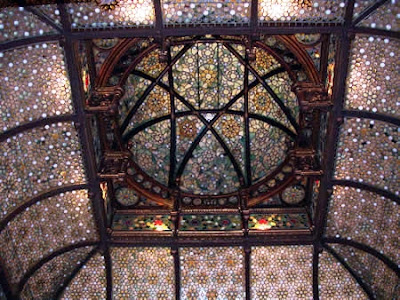

An enclosed tank on the roof provided running water. Tilden had the convenience of an elevator and his cook enjoyed a “French range.” Tilden’s renovations cost him about $500,000. The dining room alone, which was “finished in gilt,” according to the Tribune, cost $40,000. John LaFarge and Donald MacDonald created stunning stained glass ceilings.

|

| MacDonald's stained glass dome remains an architectural highlight today -- http://www.apartmenttherapy.com/warm-decor-in-the-national-art-107845 |

Interestingly, Tilden retained the two entrances—not, as might be expected, as a main entrance and a service entrance—but, as pointed out by the New-York Tribune, “with an eye to political contingencies.”

“One,” said the newspaper “was for everyday use; the other was occasionally found serviceable at political gatherings.”

|

| The elaborate entrance above the stoop was, assumedly, the one used for "political gatherings." -- photograph from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York |

Six years after the house was completed, there was apparently water seepage in the basement. Tilden hired Edward Van Orden to install water-tight flooring in the cellar. It was an expensive proposition, amounting to nearly $25,000. The contractor would discover that Samuel J. Tilden accepted nothing short of what he paid for.

While the work was being done, Tilden made payments to Van Orden amounting to $13,079. And then the flow of cash stopped. Van Orden took his employer to court in June 1885, suing him for $10,261. He may have forgotten that Tilden was one of the country’s most respected and successful lawyers.

Tilden turned the tables. The Sun reported on June 9 that his defense was that “the work was badly done, so that he had to employ other persons, at an expenditure of $12,147 to make a good job of it.” Tilden countersued Van Orden for that amount, plus $1,000 in damages from the work Van Order did in the cellar.

Samuel J. Tilden died the following year. From his massive estate he left $2 million to the New York Public Library and 20,000 volumes from his own library. The house remained in the Tilden estate, becoming home to the Tilden Trust for several years,

|

| The mansion as it appeared in 1907 with the elaborate stoop and entrance at the left removed -- Brentano's "Old Buildings of New York City" (copyright expired) |

Litigation of the Tilden will resulted in the mansion on Gramercy Park being liquidated. On May 10, 1899 it was sold at auction for $180,000 to Charles D. Sabin, the husband of Tilden’s niece, the former Susie Tilden. The New York Times reported “Mr. Sabin declined to say what he would do with the house, his answer to inquiries being ‘I do not know.’”

Sabin’s plans for the house did not include moving in, however. The grand home became “The Tilden,” an upscale rooming house.

On November 11, 1900 an advertisement in the New-York Tribune offered a “beautiful suite facing park; private table; exceptional table,” in “Governor Tilden’s Mansion." A year later the same newspaper would advertise rooms for $7, “special rates for families.”

The tenants were upscale, like Dr. and Mrs. J. Whitney Barstow whose daughter Margaret Macdonald Barstow married Leonard Stuart Robinson Hopkins in February 1900. The society wedding took place in St. Thomas’s Episcopal Church on Fifth Avenue and the reception followed in the Tilden mansion.

Naval Commander Charles Herbert Stockton lived here in 1903 when, on April 3, Washington announced his appointment as naval attaché at the United States Embassy in London. The New-York Tribune called him “one of the best known officers of the service.” He wrote the “Manual of International Law” used by the military.

|

| Vaux's use of materials resulted in a vibrantly colorful facade -- photo by Alice Lum |

By now Calvert Vaux’s outstanding façade was less than remarkable as trends changed. The New York Times surprisingly opined on May 11, 1899 “The Tilden house does not differ particularly in its exterior from the other fine dwellings on Garmercy Park."

Helen Henderson said “It is readily distinguished for its curious façade…It is a refined example of what was considered the quintessence of elegance in those days, and was much admired for its sculptured front; everything about it—the style of its iron work, the rosettes in the ornament, the variations in colour, the bay windows, and the pointed doorway and windows—suggests the Centennial period of domestic architecture, considered a vast improvement over the Georgian, which it succeeded, and in this case replaced.” (Ms. Henderson was obviously unaware of what it replaced.)

By 1905 the National Arts Club had outgrown its headquarters at No. 37 West 34th Street. On Friday March 24 the Tribune reported that the club had purchased the former Tilden residence. “The buyer will convert the premises into a club and studio building by erecting a studio annex to the present structure.”

The mission of the National Arts Club was to “stimulate and promote public interest in the arts and educate the American people in the fine arts.” Member and first President of the club, George B. Post, set to work designing the addition, which would replace Tilden’s extensive gardens. The 12-story building would provide studios with northern light across the park to artists.

The New York Times reported that “The Tilden mansion will be altered somewhat to fit the requirements of the Arts Club.

The main entrance will be into the basement, like that of the adjoining

Players Club; the smaller entrance with its outer stair leading to the first floor, will remain.

This is to be a special entrance for the ladies of the club, taking them directly by a second flight to their own little suite of apartments on the second floor.

“The dining room in the rear will have a skylight over it and form part of the picture galleries, which will extend quite through to Nineteenth Street, when the large studio-apartment annex is built.”

|

| photo by Alice Lum |

Interior work on the Tilden residence revealed passages and stairways that led to romantic stories of the politician having escape routes built into the mansion in case of assassination attempts by the Tweed Ring. On August 26, 1905 George W. Smith, for close friend of Tilden, sent an exasperated letter to the Editor of the New York Times dispelling the rumors.

Regarding the “secret staircase” he explained “To avoid the noise of the street, he planned his sleeping quarters in the rear of the new building, and for the sake of convenience he had an inside stairway with a door and plainly visible knob, built from his bathroom to that of his valet, immediately overhead.”

The underground tunnel was also explained away. “To provide accommodations for a yearly supply of fuel and a wine cellar of suitable size…a vault connected with the main cellar was constructed under the garden. To supply the furnace arrangement with fresh air, a tunnel four feet in diameter was built along the easterly wall of the house. This was all done seven years before the “ring” troubles appeared.”

|

| In 1925 The Players (foreground) and the National Arts Club dominated Gramercy Park South -- NYPL Collection |

Throughout the century the National Arts Club welcomed a wide range of members, including three United States Presidents—Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson and Dwight D. Eisenhower—as well as noted architects, painters, sculptors and performing artists.

By the 1970’s the building was showing its age. A restoration of the MacDonald domed glass ceiling was executed by Albinius Elskus, a stained glass artist and club member.

But serious deterioration continued. In 1999 Ehrenkrantz, Eckstut & Kuhn conducted architectural studies, in concert with engineering studies by Robert Silman Associates. Their findings recommended a $2 million stabilization of the façade.

Five years later nothing had been done. In 2004 concerned Arts Club members complained that “pieces of the clubhouse are now literally falling to the street.” Citing a lack of interest by the club’s management, they reached out to city agencies, newspapers and preservation groups for help. In a letter to city governmental agencies the members complained “Additionally, the elegant interiors have also been deteriorating. In one example, a front parlor wall charred black in a fire five years ago was never restored.”

|

| Calvert Vaux's stunning facade was suffering alarming deterioration in 2004 -- http://concernednac.homestead.com/ |

Then-president of the club, O. Aldon James received the brunt of the blame for the sorry state of affairs. Of the 35 apartments in the annex, he, his brother John and their lawyer friend Steen Leitner used many for storage space. Ceilings collapsed from water damage and studios were piled high in trash. In the meantime, Aldon was under investigation for “alleged financial irregularities at the club."

Aldon finally stepped down in June 2011, after a quarter of a century in office, and renovations began on the apartments. A spokesman for the club said that “Everyone will want to look at them, but the people who will really want to rent them will be those with a true appreciation for the history of New York.”

Samuel J. Tilden’s remarkable double mansion survives.

It is a rare example of Victorian Gothic residential design in the city and the scene of an amazing page of New York and American history.

|

| photo by Alice Lum |