|

| photo by Alice Lum |

By 1871 development on the Upper East Side was well underway. With the Civil War ended construction here had resumed. Rowhouses and small commercial buildings were appearing and along the riverfront grittier industries like factories and saloons had sprung up. There was a serious lack of houses of worship for these new residences; a fact that did not escape the attention of Rev. William Ferdinand Morgan, rector of St. Thomas Church far downtown.

Under Morgan St. Thomas’ prestigious new church building on Fifth Avenue and 53rd Street had been completed the year before. Now he turned his attention to the community uptown. For decades, as Manhattan’s residential areas spread away from its churches, chapels were constructed as extensions of the parishes. He proposed to move the existing St. Thomas Chapel to a new location.

In December 1871 three buildings plots were acquired on East 60th Street between Third and Second Avenues. On Christmas Day the following year The New York Times reported on the consecration of the new chapel by Bishop Henry Codman Potter four days earlier. “This chapel is admirably located, and is not intended to be a poor church for poor people, but an attractive and well-appointed sanctuary for all, the rich and the poor, the high and the low, who may seek the consolations of the Gospel.”

The completed church had cost about $34,000—a significant $625,000 by today’s standards. The newspaper noted that it “is paid for to the uttermost farthing, and is to be forever free.” The decision of St. Thomas not to charge pew rents was judicious one. Although the article stressed that the chapel was not to be a “poor church for poor people,” the community was still middle-class at best. Charging fees to worship could have seriously deterred potential members.

When St. Thomas’ Protestant Episcopal Chapel celebrated its first anniversary in December 1873 there were already signs that a larger structure was needed. Calling it a “neat and comfortable little edifice,” The New York Times noted on December 22, 1873 that the seats were “well filled.” In his address, Bishop Potter noted “The chapel was surrounded…with a larger population than the old Church of St. Thomas when it was built down town” and “there were general evidences of prosperity.”

|

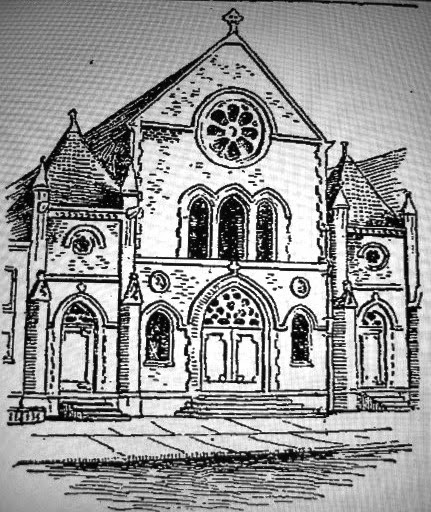

| The New York Times published a sketch of the anticipated chapel on November 4, 1894 (copyright expired) |

The number of congregants increased over the next two decades and by the beginning 1894 of plans were on the table to demolish the two-year old building and erect a “larger and better one.” The trustees of St. Thomas possibly would have made do with the original chapel had it not been for Mrs. J. S. Linsley whose mansion off Fifth Avenue was at No. 3 West 50th Street. The New York Times reported on November 4, 1894 that “Mrs. Linsley took much interest in the church and in the work being carried on there by Dr. W. H. Pott, and noticing the discomforts of the old building, offered to build a new church. Her offer was accepted and the old building was torn down last Summer, and the new one is fast approaching completion.” She intended to present the new chapel as a memorial to her son.

C. E. Miller was chosen to design the chapel. Like many late 19th century architects, he did not feel obligated to limit himself to a single style. For his 64-foot wide church he splashed his generally Sicilian Romanesque design with Gothic Revival—resulting in a charming structure The New York Times called “in the Venetian style of architecture.”

Miller used buff- and orange-colored brick trimmed in stone for his perfectly symmetrical chapel. An opalescent glass rose window hovered above three clustered lancet windows over the entrance. The interiors were finished in oak and 36 stained glass windows “insure perfect light and ventilation,” according to The Times. Among them was an 8 by 12 foot chancel window, a reproduction of Hoffman’s “Christ in the Temple,” which was flanked by two 8-foot square windows representing the sky. Another Hoffman-inspired window, the “Annunciation,” was 9 feet high. “The other windows will be of opalescent glass set in carved oak frames and supported by stone columns,” announced the newspaper.

Delicate spidery Gothic tracery, imitation marble columns, and half-groined arches adorned the space. The floors were tiled and the steps to the chancel were of marble. Capable of seating 700 worshipers, it was deemed “one of the handsomest in the city for a church of its size.” Interestingly enough, the completed chapel cost $30,000--$4,000 less than the original structure.

It was consecrated on April 21, 1895 by Bishop Potter; but finishing touches would continue for several years. It would be two years before the new organ was installed. At its dedication in November 1897 the organist from St. Thomas Church, Walter C. Gale, and his assistant, Frank A Warhurst, played. The church sent its quartet along as well to add to the music provided by the chapel’s own vested choir.

Directly behind the chapel were the parish house and the mission house, on 59th Street. By now the upscale tone of the Fifth and Madison Avenue neighborhoods were pushing eastward; but the population around St. Thomas Chapel still included those in need. The Churchman noted the outreach provided by the chapel on June 18, 1898. “The mission work here is under the direction of the Helping Hand Association, a society which has under its charge the chapel, the mission house, the day nursery, the diet dispensary, the Employment Society and other forms of parochial activity.”

In the mission house, said the article, “the ground floor is occupied by a diet kitchen, where cooking classes are held and from which good food is distributed to the sick poor of the parish.” Girls were taught simple cooking “as are possible in their own tenement house homes.” There was also a day nursery, so mothers could work. The Employment Society provided some of these women work sewing and doing “days’ labor.”

The diet kitchen was an early form of today’s soup kitchen. According to The Churchman, “Thousands of quarts of soups, gruels and milk have been given away, and this judicious distribution of nourishing food has, in many cases, prevented serious illness.”

The mission work here developed into an interesting concept in 1910 when a “model tenement” was opened at No. 410 East 65th Street. Neighborhood girls visited the apartment and were taught housekeeping—cooking, ironing and bed making—in a virtual environment. According to the New-York Tribuneon March 27, 1910 “There are four rooms, and in these four rooms is everything necessary for a well conducted home…Nothing is in the model flat that is superfluous. The bedroom has its bureau, a chair or two, a bed with snowy bedding and a trundle bed hidden under the big one. In the small parlor are a desk, chairs and a couch covered with blue denim, which can be used as a bed. Rag rugs, easily taken up and shaken, are on the floor.”

According to an instructor, Harriet Jessup, “We want to show the girls, and through them their families, that household things can be simple and inexpensive and yet very pretty. We want to show them how much more attractive is a flat with a little furniture, well chosen, than rooms all cluttered up with heavy upholstered chairs, unnecessary wall pockets and thick carpets to harbor germs.”

The year 1931 was pivotal in global history as war ignited and the rumblings of other war threatened. On April 14 that year the Spanish monarchy was declared overthrown and a provisional government took over. In September Japanese soldiers disguised as Chinese outlaws would dynamite the South Manchurian Railway. Rev. Frederick Swinglehurst took the pulpit at St. Thomas Chapel on May 31 and warned the congregation about glorifying war. Swinglehurst knew what he was talking about, having served in World War I during which he was gassed and wounded.

He told the congregants that war was incompatible with religion and civilization, both from the viewpoint of a churchman and a soldier. “Despite all the assertions of literature and the press, our civilization, erected in the accumulation of genius, was swept into an undeniable refutation of itself by the recent war. It was not a struggle of people against people, nor of a group against another, but the outcome of a highly commercialized and materialistic outlook.”

Unfortunately for the world, those in power did not share Rev. Swinglehurst’s views.

At mid-century architectural design tastes changed in favor of flat surfaces and sleek space age modernism. In the 1950s Urban Renewal began sweeping the country, eradicating blocks of Victorian structures to be replaced by shoebox office buildings and cookie-cutter homes. Directly in the fad's crosshairs, the 19th century architecture of St. Thomas Chapel was considered passé. C. E. Miller’s charming structure was not demolished; but it might as well have been.

The opalescent class rose window was trashed, replaced by a modern composition; the lancet windows were removed and covered over; and a slathering of thick stucco covered the tapestry-like brickwork and stone. An aluminum cross was affixed to the modernized façade.

|

| In 1959 little hint of C. E. Miller's handsome design remained. http://www.nycago.org/Organs/NYC/html/AllSaintsEpis.html from St. Thomas Church archives. |

In 1963 the name of the chapel was changed to All Saints and two years later became an independent parish church. Nearly four decades later the architectural blunder made in the 1950s was apparent to nearly everyone. The parish turned to architect Samuel G. White of Buttrick, White & Burtis to reverse the damage.

The architect spent years working with All Saints in deciding which direction to take. White’s solution was not to replicate Miller’s original design—a not impossible but certainly difficult and highly costly project—but to create a new look with a 19th century feel. The resolution was to remodel the façade in a 21st century take on Carpenter Gothic; the style familiar to most Americans through Grant Wood’s iconic painting “American Gothic.”

|

| photo by Alice Lum |