|

| photo by Alice Lum |

James Wright Markoe earned his medical degree in 1885 at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. The strapping young man was as physically-inclined as intellectually. The New-York Tribune would later say of him “As a young man he was an athlete. He spent much of his spare time in the gymnasium boxing, and was classed as one of the best amateur boxers at that time.”

Boxing would soon take a back-seat to a more humanitarian interest, however. Following graduation he traveled to Munich where he spent a year advancing his medical studies. While at The Frauenklinik of Von Winkel learning obstetrical procedures, he and fellow student Samuel W. Lambert recognized the need for a clinic in New York to help needy mothers-to-be.

Manhattan at the time was filling with immigrants who struggled to survive in grimy, crowded tenements. Unsanitary conditions coupled with the inability to pay for medical help resulted in a catastrophic infant mortality rate within the tenement community. Upon the doctors’ return to New York they established the Midwifery Dispensary in 1890.

The clinic opened in a house at No. 312 Broome Street and shortly thereafter was combined with the long-defunct Society of the Lying-In Hospital. Expectant women flocked to the new facility, quickly resulting in the need for an expanded and improved space.

Dr. James Markoe not only practiced medicine among wealthy society, he was a member of it. He held memberships in the exclusive Metropolitan, Century, Racquet and Tennis, and New York Yacht Clubs. For years he was a vestryman in the highly-fashionable St. George’s Church on Stuyvesant Square.

Among James Markoe’s moneyed patients was millionaire J. Pierpont Morgan. Markoe not only became his personal physician, but a close friend. It was a friendship that would create financial advantages for Markoe’s pet project.

In 1894 the Hamilton Fish mansion at the corner of 17thStreet and Second Avenue was purchased and converted for the hospital. The New York Times said “In this fairly commodious house the work of the association has increased” and quickly the building was not sufficient to care for the stream of patients. By 1895 the push was well underway to expand the Lying-In Hospital and build a new facility. On March 14 of that year Mayor William Lafayette Strong introduced a bill appropriating $12,000 to the Society of the Lying-In Hospital—about a quarter of a million dollars in today’s money.

“The Mayor asked any one who had anything to say in opposition to the appropriation of $12,000 for the Lying-In Hospital to state their objections first,” reported The New York Times. “No one responded, and the Mayor said that he was not surprised, as it would be a queer kind of man who would oppose such a charity.”

Private donations came in; but at a rather disappointing rate—at least to the mind of J. Pierpont Morgan. In 1896 donors had given $53,738; not nearly enough to even consider a new structure. On January 4, 1897 Morgan penned a letter to William A. Duer, the President of the Society of the Lying-In Hospital.

Dear Sir: I have for some time thought it desirable that your society should erect upon the land recently purchased from the estate of Hamilton Fish a suitable building for the needs of the hospital.

Being of this opinion, I have had preliminary studies made by Mr. Robertson, as architect, which I think will be satisfactory to your Board of Governors; if not, they can easily be modified.

The architect, “Mr. Robertson,” was the esteemed Robert Henderson Robertson. Morgan had taken it upon himself to choose the architect and lay out stipulations on the building’s construction. His letter would go on to explain why he had every right to do so:

I assume that the cost of the building will be about $1,000,000, which sum I am prepared to donate for that purpose. The only conditions that I make are:

First—That before the building is erected it shall be apparent that the income of the hospital, from endowment or other sources, render it in all human probability sufficient to meet expenses, after the new building shall be erected.

Second—That the plans and the carrying out of same, from a medical point of view, shall be satisfactory to Dr. James W. Markoe. Yours very truly. J. Pierpont Morgan.

Morgan had put Markoe fully in command of the design of the medical aspects of the structure. The New York Times quickly published Robertson’s preliminary plans.

On January 15, 1897 the newspaper said “The proposed new hospital building will be a handsome and imposing structure of granite and pressed brick, thoroughly fireproof, ten stories in height…It will have every improvement and convenience known in modern architecture and applicable to hospital purposes. It will have accommodations for 250 patients, and, as the patients are usually discharged in two weeks, the total capacity of the hospital will be about 6,500 a year, while the outdoor service is practically unlimited.”

Invigorated by the sudden windfall, the Governors of the Society set to work to raise additional funds. Morgan’s stipulation was, after all, that the hospital be financially independent. “But they seem nowise afraid of the future,” reported The New York Times. “They expect to raise not less than $1,000,000 in a reasonable time, and are even hopeful that they may exceed that amount.”

Morgan’s patronage of the hospital was possibly a factor in its becoming a favorite money-raising event among New York’s wealthiest socialites. On February 27, 1898 The Times wrote “One of the most important Lenten entertainments to which society people are now looking forward will take place on the afternoon and evening of Saturday, March 19 at the Waldorf-Astoria. The Society of the Lying-In Hospital of the City of New York is to be beneficiary, and the fashionable set have come out in force to give it their patronage.”

The article listed the ladies who put their significant social heft behind the affair, including Caroline Astor, Mrs. John Jacob Astor, Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish, Mrs. Ogden Mills, Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs, Mrs. Frederic W. Vanderbilt and other prominent names like Rhinelander, Sloane, Lorillard, Whitney, Stokes, Baylies, Dodge and Morton.

The old Fish mansion was demolished and erection of the hulking new hospital began. Morgan’s initial $1 million donation proved insufficient. The New-York Tribune noted that “Because of a rise in the price of structural materials, Mr. Morgan subsequently gave $500,000 additional.”

|

| The building neared completion in August 1900 -- New-York Tribune, August 13, 1900 (copyright expired) |

By August 13, 1900 the building was taking form and the New-York Tribune updated readers on the progress. “The exterior of the main structure lacks only a few additions in the way of casements and doors to make it complete, and the gangs of men employed upon the central superstructure are busily at work on the iron frame.”The newspaper was not especially impressed with Robertson’s design. “The main building arrests the attention of the passer by not so much because of its architecture, which is markedly lacking in ornate features, but because it stands in such striking contrast with its immediate neighborhood. It towers high above the adjacent dwelling houses, and its walls of gray Ohio limestone and bright red brick stand out sharply in comparison with their dingy brownstone.”

In explaining to its readers the purpose of the new building, the newspaper waded into what, by a 21st century viewpoint, was a swamp of potentially-offensive verbiage. “The erection of this great hospital is perhaps the logical outcome of the tremendous racial changes which have been going on in that district of the city during the last thirty or forty years. The influx of a vast foreign element has altered what was once an exclusively residence part of the city to one occupied largely by tenement dwellers. The increasing congestion of this kind of population naturally demanded hospitals, and the need of a great maternity hospital became most imperative.”

The hospital opened in January 1902; a stately Renaissance Revival structure surmounted by a Palladian pavilion. Although the Tribune complained that it lacked ornamentation, Robertson creatively included sculptures of chubby babies within the spandrels, in medalions, and within the friezes.

|

| Adorable bas reliefs of swaddled infants appear along the facade -- photo by Alice Lum |

The first floor housed the offices of the doctors, the second and third floors were for “the clerical department” and accommodations for 52 nurses, while the fourth, fifth and sixth floors housed the wards. The kitchen and laundry were on the top two floors and a solarium was on the roof.

|

| Robertson brought the design to a dramatic climax with the Palladian pavilion -- photo by Alice Lum |

The paint was barely dry before the expectant mothers filed in. Eight months later there had been 1,278 applicants seeking ward treatment--an average of 160 per month. In the meantime, doctors going into the field to treat the impoverished women in their homes found their jobs not always the easiest.

On August 2, 1902, just eight months after the new hospital opened, the husband of Jennie Davis rushed to get medical help as she went into labor in their apartment at No. 368 Cherry Street. Two doctors of the Lying-In Hospital, Dr. Rose and Dr. Tailford, arrived with a visiting physician. Word spread among the concerned neighbors that Rose and Tailford were students who were observing and helping a veteran doctor.

When the visiting physician left the woman in the care of Rose and Tailford, whom the neighbors supposed were merely students, a near riot broke out. The New-York Tribune reported “After examining the woman, the one the neighbors thought was a physician went away on other business, leaving the supposed students in charge of the case. Relatives and neighbors crowded in and objected to their way of treating the woman.”

Tragically, in the uproar that followed the doctors were interrupted in their treatment and Mrs. Davis died. “The crowd grew excited and threatening, and in the excitement the woman died before the child was born,” said the newspaper. The enraged group, now a rabble, seized the doctors and threw them down the tenement stairway.

|

| The poorest of New York City's citizens passed through a magnificent entranceway -- photo by Alice Lum |

James W. Markoe continued on as Medical Director and attending surgeon at the Lying-In Hospital. In his will J. Pierpont Morgan bequeathed Markoe an annual income of $25,000 for life “because of his service at this hospital,” as reported in theNew-York Tribune.

On Sunday morning April 18, 1920 as services at St. George’s Protestant Episcopal Church drew to a close, Markoe was walking up the aisle with the collection plate. Suddenly Thomas W. Simpkin, a stranger to the congregation, rose from his seat near the rear of the church and fired a bullet into the forehead of the doctor. The shooter was described in The New York Times the following day as “a lunatic, recently escaped from an asylum.”

Within seconds the life of the celebrated surgeon, the victim of an irrational act, had been snuffed out. His will instructed that had his wife and daughter not survived him, his entire estate was to be left to his beloved Lying-In Hospital.

|

| Close inspection reveals infants popping up throughout the ornamentation -- photo by Alice Lum |

As the years passed, John Pierpont Morgan, Jr. was concerned about the long-term stability of the hospital his father had so generously provided for. He recruited John D. Rockefeller, Jr.; George F. Baker, Sr.; and George F. Baker, Jr. to join forces in establishing an association with New York Hospital. Upon the subsequent opening of the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center in 1932, the Lying-In Hospital moved out of the Second Avenue building. It became the more modern-sounding Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of New York Hospital.

In 1985 the architectural firm of Beyer Blinder Belle renovated the building—already added to the National Register of Historic Places—as offices and residential spaces. Like the New-York Tribune in 1900, the “AIA Guide to New York City” was reserved in its assessment of the design, calling it “boring until the top.”

|

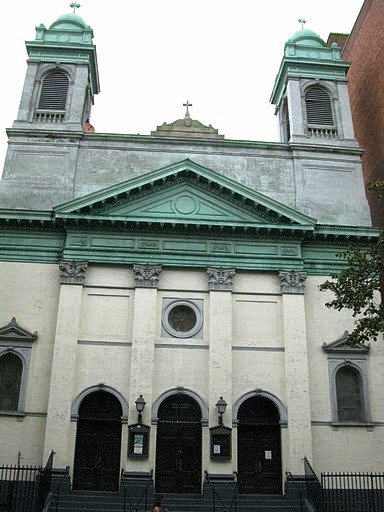

| photo by Alice Lum |

The “top,” however, makes up for the “boring” and the delightful limestone babies—reminders of the building’s original purpose—are guaranteed to bring a smile. |

| photo by Alice Lum |

thanks to reader Alan Engler for suggesting this post